Photo by Xuan Nguyen on Unsplash

Bugs in real life

Bugs are inevitable evil in any system. No matter how excellently the system is designed, how well it is implemented, and how intelligent the engineers behind the system are, bugs can occur.

One of the primary goals of any test engineer is to show that system has some errors and risks - and deliver it before the system goes to production.

Bugs can emerge in many different forms: some of them are relatively easy to identify and fix. But some bugs are hard to find even by experienced developers.

One of such bugs is the concurrency bug. Systems are typically tested in a single-user mode so that concurrency bugs can slip by the testers. Some tests (e.g., performance) can help find concurrency issues - but in many cases, these tricky bugs are identifiable in production with an actual user workload and conditions.

Concurrency bugs are often associated with timing issues in single-machine multi-threaded systems. But as systems are getting more complex and distributed, the number of distributed-concurrency problems is increasing.

Tanakorn Leesatapornwongsa et al. have done tremendous research about the nature of the distributed concurrency bugs in their paper: “TaxDC: A Taxonomy of Non-Deterministic Concurrency Bugs in Datacenter Distributed Systems”.

In this blog post, I will share my insights after reading this paper.

What is distributed concurrency bug?

The points of the study were four distributed systems:

Researchers performed an in-depth analysis of 104 distributed-concurrency bugs from the public bug-tracking systems.

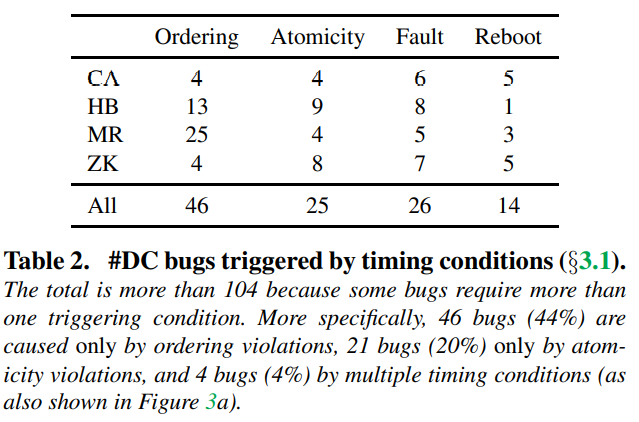

Timing conditions

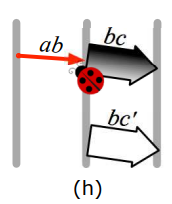

Most distributed-concurrency bugs studied in the research happened due to untimely delivery of messages, by untimely faults or reboots, or by a combination of both.

Timing bugs can be divided into two categories:

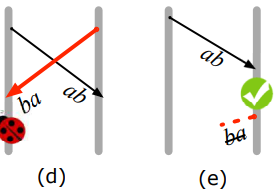

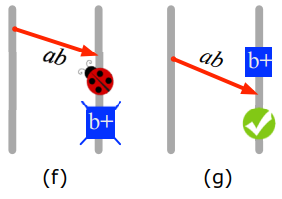

- order violation: when a message comes earlier (later) than another expected event

- atomicity violation: when a message comes in the middle of a set of events

It turns out that there are a lot of possible causes for bugs:

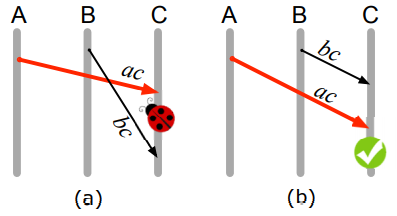

- When node B sends task-init message node C, node A sends task-kill message to node C. As a result: task-kill message comes before task init message.

- When cluster-join message from node B is sent to node C before a security-key message from node A to B is arrived at B.

- When node A sends the task-kill message to node B and node B sends task-complete message to node A. If the A->B message comes before B->A message is sent - a bug will not occur. But in fact, the opposite situation can happen.

- When task-kill message from A->B comes before B finished an internal computation task.

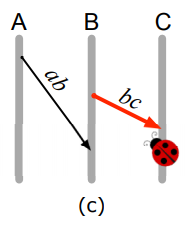

- When node A sends task-kill message to B in the middle of the transaction between nodes B and C. As a result, when B will try to re-run commit task - C will throw an exception - and the transaction will never be finished.

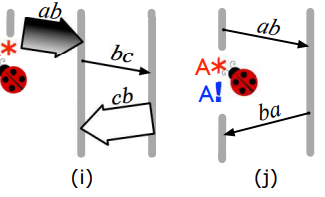

Fault and reboot timing bugs can also happen:

- when node A sends a job to node B and then crashed before the job is completed by node B. As a result, node A will decline job-finished message from node B just because node A does not have any information about the task.

Fixes

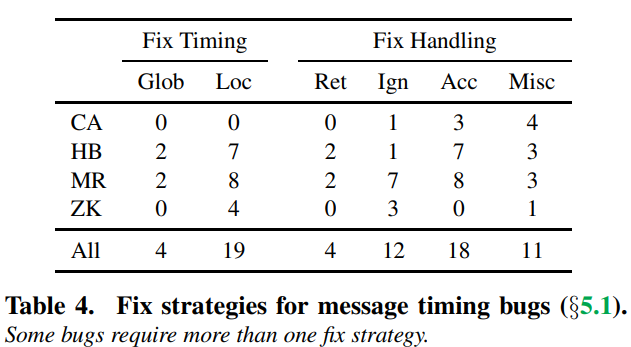

Fix strategies for message timing bugs

Distributed concurrency bugs can be fixed either by updating message handling or by changing message timing itself. Only 20% of the whole amount of message timing issues can be fixed by adjusting timing. Most of the problems (83%) were fixed using local synchronization comparing to a global one. Fixing message handling can be done in multiple ways:

- retry untimely message later

- ignore untimely message at all

- accept untimely message by re-using existing handlers

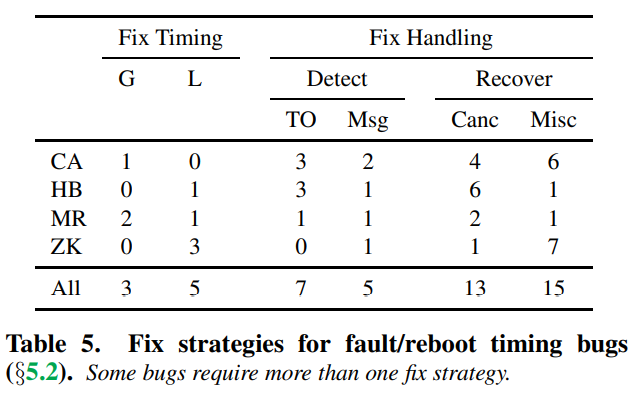

Fix strategies for fault-reboot timing bugs

Global/local synchronization fixes are a rare case here. In other cases, fixes were done using timeouts, ignoring events, and retry.

Misconceptions and lessons learned

As a part of the study, the authors show several popular misconceptions about distributed-concurrency bugs:

- One hop is faster than two hops. Some developers may assume that an event from one node will always be faster than an event that travels through two nodes.

- No hop is faster than one hop. In this case, the developer assumes that local events will always come faster than events from other nodes.

- Atomic blocks cannot be broken. developer believes that atomic performing atomic blocks on resources will always guarantee that concurrency bugs will never happen. But in fact, such blocks can be broken by untimely arrival of kill/preemption messages in the middle of the atomic block

- Enough states are maintained. Untimely event can potentially corrupt internal system state on the node, so it is not possible to solely rely on event history even if it logged

Lessons learned from the study:

- testing of distributed systems should include fault injections and multiple protocols as input conditions

- good specifications can reveal concurrency issues at the design phase of development

- there are no automatic tools for detecting distributed-concurrency bugs (for now)

Conclusion

The study clearly shows that distributed systems provide many values (availability, partition tolerance, consistency) and add way more complexity levels.

Modern application rarely involves creating giant distributed systems “from scratch.” In most cases, you will use one or more significant and “proven” systems to build your own.

Immense systems and storages like Cassandra or ZooKeeper provide some level of assurance that they will work as expected. But you never will be 100% sure that the system will work correctly in production deployment.

So testing now, as always, is crucial. Knowing the root causes of the issues can help you identify potential problems during your system’s design.